Nowadays, the negative connotations associated with tattoos have largely dissipated. Sporting a tattoo has become almost mainstream, no doubt the elevation has been assisted by the numerous rock stars, athletes and celebrities who have a penchant for ink and a wide fan base to boot.

As a person with numerous tattoos, the subject of copyright never crossed my mind, either before or during my time under the needle. But should it have?

With the business of tattooing booming, so does the demand for quality work. Tattooists are considered artists, and rightfully so.

Protecting your copyright in Australia

In Australia, an artist’s work is protected by copyright without requiring the artist to formally register their work.

But to have that protection, certain criteria must be addressed, namely:

the artist must be an Australian citizen or resident; and

the work must be an original artistic work demonstrating intellectual effort (ie. it is an original painting, sculpture, drawing, engraving or photograph, whether the work is of artistic quality or not); or

the work must be an original work of artistic craftsmanship.

Copyright may also subsist in an original compilation of works and, in some cases, an analysis of whether copyrights exist is a question of fact and degree.

Provided the copyright criteria is met an artist, tattoo or otherwise, does not have to be a professional nor is their work required to be published for an enforceable copyright to be created.

In Australia, copyright subsisting in a tattoo artist’s work, as opposed to a more conventional artist’s work, has not been considered by a superior Australian court.

Perhaps this has something to do with the nature of tattooing itself because:

First, the client generally dictates what they want the tattooist to put on their body, which may be a trending concept or something that the client has seen on another person. Ultimately, the client gets the last say as to what they want permanently etched in their skin, rather than the tattoo artist.

Second, unlike other artistic works, tattoos are arguably sold with an implied licence for the customer to display the tattoo in public and allow photographs of it. But, again, every case falls on its facts and there will be scenarios where a tattoo artist sells their work to a client on the basis that it is not reproduced, copied, distributed or licensed, whether for commercial gain or otherwise.

Realistically, legal arguments will be about how far the implied licence from artist to customer extends.

In the United States of America (the USA) there have been cases where tattoo artists have brought claims for copyright infringement. For example:

Nike was sued when it used NBA player Rasheed Wallace’s tattoo in advertising material.

Warner Bros. was sued when it used Mike Tyson’s facial tattoo in the The Hangover II

Take-Two, makers of the video game NBA 2K, is being sued for the use of various NBA players’ tattoos within the game.

So far, each case has settled except for Take-Two, which is still on foot.

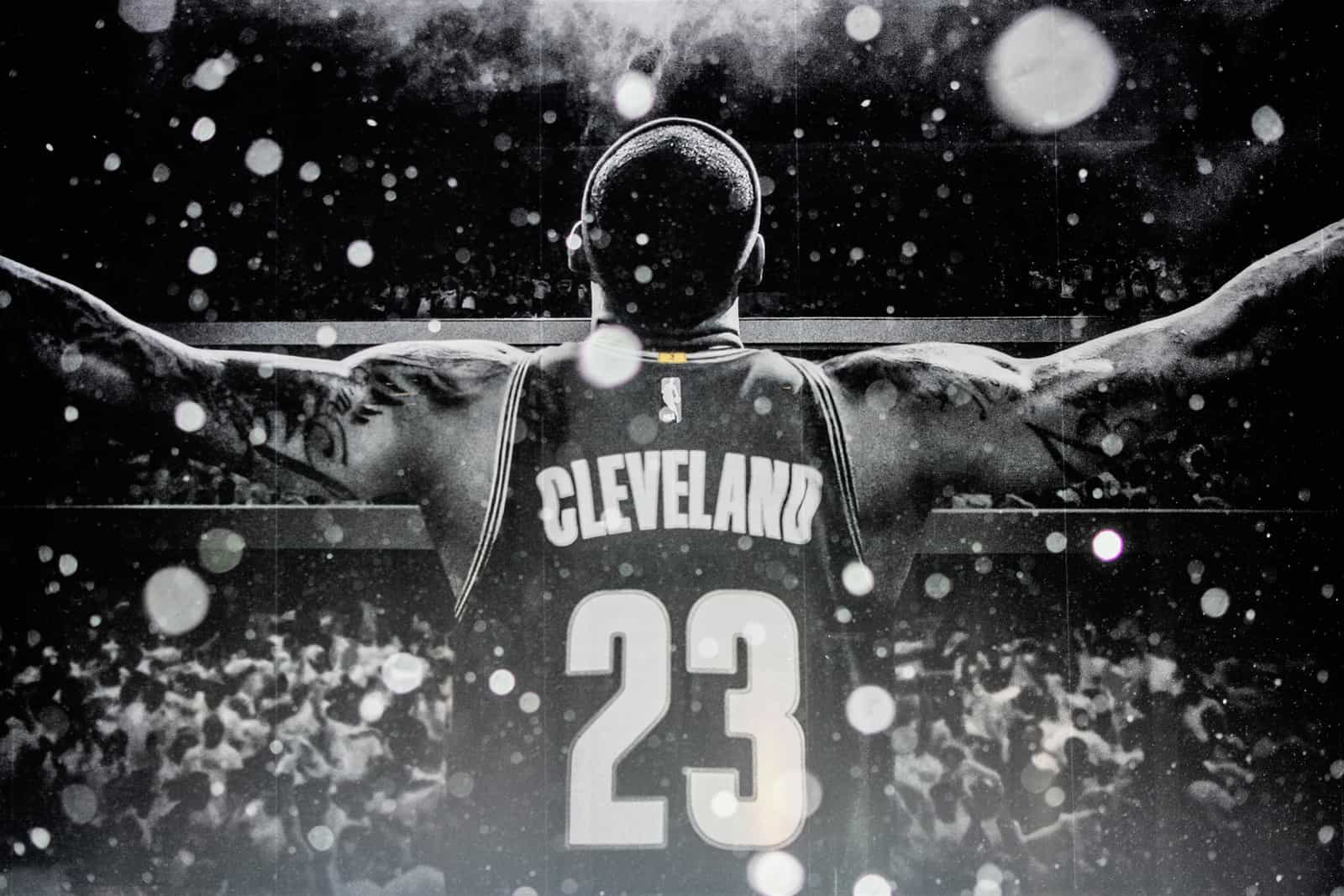

Photo by: Erik Drost (CC by 2.0)

Although there is little case law to examine a factual scenario for tattoo copyright with legal certainty, the above claims have a common theme: Each generally involves companies who have used the tattoos of celebrities for commercial purposes and each involves the artist or copyright owner suing for breach of copyright.

The US cases involve a degree of separation between the celebrity and the depictions of their tattoos. Rather than being an incidental depiction, such as a photograph or video of the tattoo wearer for their own personal use, the tattoo was the focus of a marketing or commercial endeavour. This means the tattoo is being capitalised on for commercial gain, ergo there is money involved.

For most of us the inconvenience of stardom and value of our ‘personal brand’, tattoos and all, is minimal. However, it is not so farfetched to imagine tattoo copyright gaining traction, particularly with the rise of social media.

Social media will influence the issue of tattoo copyright in three ways:

First, by giving tattoo artists a platform to advertise their work beyond the human canvasses they paint their art on. Social media enables the artist to widely display their unique style.

Second, the rise of social media influencers (who may not be a celebrity in the traditional sense, but who have a wide following and profit off their personal brand, some quite lucratively) will show off their tattoos and may even use their tattoos as part of a wider commercial image.

Third, an artist (not necessarily a tattoo artist) whose work is tattooed on a person by a tattoo artist without authorisation or licence may more easily track the tattoo artist on social media to seek remedies for copyright infringement.

In the face of the unknown, what can tattoo artists and wearers do? In the immortal words of the boy scouts: Be prepared. Here are some strategies how:

Photo by: Iburiedpaul (CC by 2.0)

For the tattoo artist

If your reputation is growing, your Instagram followers are blowing up, or you are beginning to get some high-profile clients then you should sure up your copyright to your work.

The clearest strategy to achieve this is by drafting an agreement for your client to sign prior to you inking them. You may be able to work some clauses into your existing contract.

It is also important to keep a record of your original works, whether they are preliminary sketches or completed pieces. You can do this by dating, filing and storing your work.

You should also be vigilant when a client wants a tattoo of an existing piece of art. Where possible, contact the original artist and request their permission to tattoo their work. This may be as simple as flicking them an email and it could save you down the track.

For the tattoo wearer

If you are considering a tattoo piece by a prominent tattoo artist be aware that copyright in favour of the artist may continue to subsist in the piece, and will be particularly relevant if your career is in the public eye.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bk1WJLGjNCq/?tagged=tattoo